Key Takeaways

- Charitable Remainder Trusts (CRTs) can provide you with an annual income stream to fund current expenses.

- CRTs can come with sizable tax benefits that boost your bottom line and leave more to charity.

- It’s crucial to set up a CRT correctly to get the benefits—and avoid trouble.

Substantial numbers of affluent individuals and families want to use some of their wealth to support the causes and organizations they care about most. From helping those less fortunate to facilitating scientific breakthroughs, from providing safe habitats for wildlife to sharing the arts, philanthropy is a core value for many.

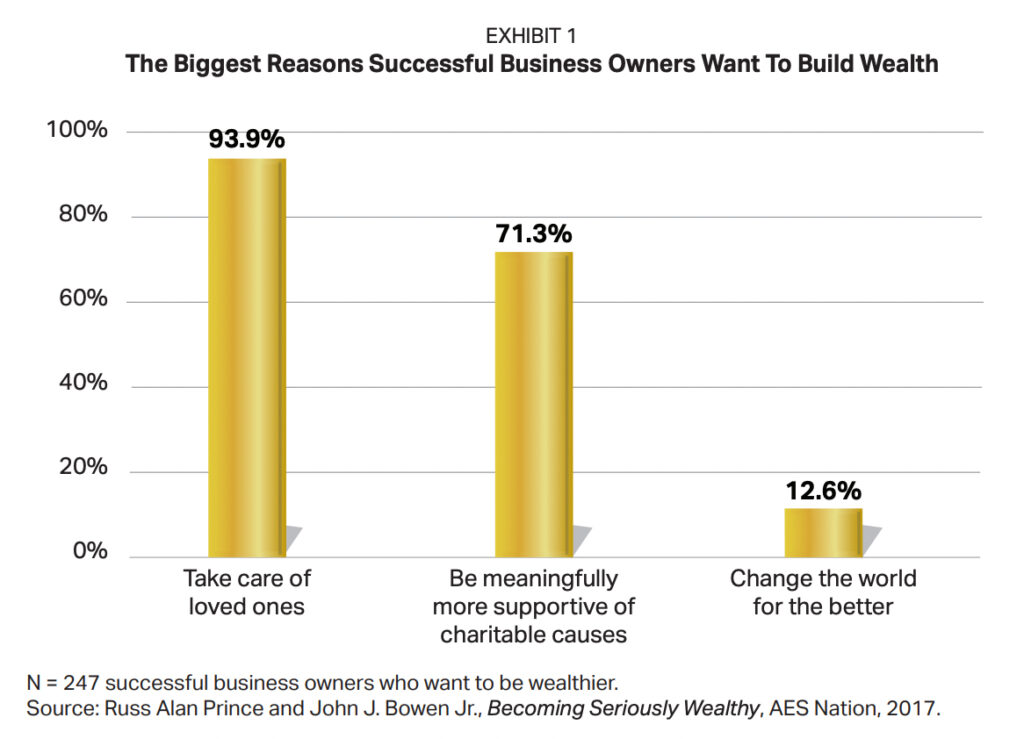

Just look at one affluent group: successful business owners. More than 70% of the successful business owners who told us they want to be seriously wealthy are tremendously charitably inclined (see Exhibit 1). They see amassing greater wealth as the means by which they are able to do more to improve the world. (They’re not the only ones seeking to have a strong charitable impact, of course. In working with the affluent for decades, we have consistently found philanthropy to be one of their most important goals.)

Of course, the affluent also know the importance of smart philanthropy—how, by using the appropriate tools and strategies, they can have a much bigger impact than they otherwise could, while simultaneously enjoying benefits that can enhance their own financial security and flexibility. In this way, the affluent seek to—as the old saying goes—“do well by doing good.”

With that in mind, here’s a closer look at one philanthropic tool that many charitably minded people and families use: charitable remainder trusts.

The ABCs of a CRT CRTs’ popularity stems from the fact that tax-wise, they are among the more powerful charitable giving mechanisms. The possible tax benefits—such as the elimination of capital gains tax on the sale of appreciated assets and potential tax-deferred growth—make charitable trusts highly appealing to many with significant assets.

Let’s start with some CRT basics.

- Income stream. You place money or appreciated assets in a CRT that you set up, which then provides an annual income stream. You can designate yourself or other people to receive that income. The income stream can last for your life or the lives of the people you designate. You can also have the income stream last for a term of years (as long as that term does not exceed 20 years).

- Tax-deferred growth. The assets in the CRT grow tax-deferred. You are taxed only on the income you receive from the CRT.

- Charitable impact. Once the term of years is up or the last beneficiary dies, the income stream stops. At that point, the assets remaining in the trust go to one or more charities you selected.

Two Caveats

A CRT isn’t right for everyone, of course—few, if any, charitable giving strategies are. Here are two things to consider if you look into CRTs:

- 1. The right intention is crucial. A CRT is an irrevocable trust. Once you put assets in a CRT,

you cannot get them back. (You can, of course, receive the income stream generated

from those assets.) That means your motivation to use a CRT can’t simply be to save

taxes—you must have a genuine charitable intent for a CRT to make sense. If you don’t,

there are other ways to minimize taxes that don’t require you to make irrevocable gifts

and give up control of transferred property. - 2. It’s not a piggy bank. At least 10% of the actuarial value of the CRT must go to charity.

That’s why the payout schedule will be determined by actuarial calculations. A CRT that

does not meet the 10% remainder requirement is not a qualified charitable remainder

trust—and will lose its tax benefits.

For the avoidance of doubt, it is possible that the CRT has nothing left to pay the charity. That is permissible as long as at the onset, using IRS-prescribed actuarial rules, the charity should theoretically receive its intended actuarial share.

Types of CRTs

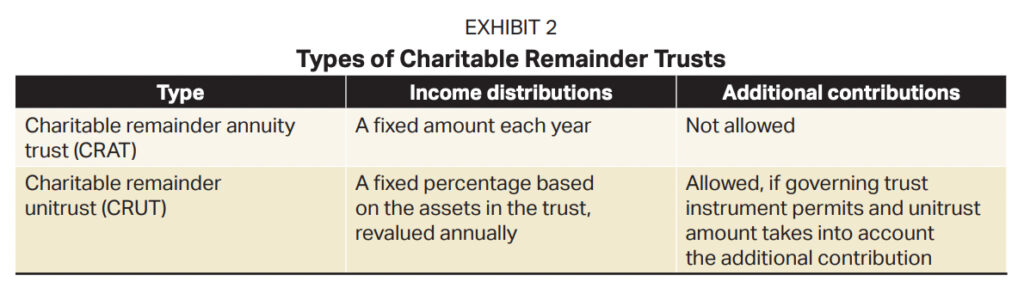

The CRT landscape is divided into two main types of trusts (see Exhibit 2).

- 1. Charitable remainder annuity trusts. With a CRAT, you (or the recipient you designate) receive(s) a fixed dollar amount from the trust every year. However, once you set the amount, it cannot be changed. Say, for example, you set the annual amount at $15,000. That is all you can receive every year, even if the assets in the CRAT are growing rapidly. Also, you cannot add new assets to a CRAT after it’s set up and funded.

- 2. Charitable remainder unitrusts. With a CRUT, you (or the person you designate) receive(s) a percentage of the current value of the assets in the CRUT. Example: You specify that you want to receive 6% of the assets in the trust annually. Every year, the assets are reappraised and you get 6% of that amount. Another difference: You can add more assets to a CRUT over time.

What can you put in a CRT?

You can use a wide variety of assets to fund a CRT. Some examples include:

• Cash

• Stocks and bonds

• Some types of closely held stock (such as LLCs, but not S Corps, as a CRT is not a permissible shareholder of an S Corp)

• Partnership interests

• Real estate

• Artwork and collectibles

Important: While a CRT is an irrevocable trust, it is probably wise to make it as flexible as possible. For example, you might want to be able to replace the managers of the assets in the trust. Such terms can be written into the trust.

Case Studies

To see the potential power of a CRT, consider these two examples.

Case study #1: Selling a small business

A charitably inclined small-business owner and spouse in their late 50s want to retire. The business, structured as a limited liability company, is a portfolio of passive investments worth $21 million. It started from scratch and has zero basis.

If the couple sold the business directly and paid taxes of 23.8%, they’d face a tax bill of approximately $5 million. Instead, they contribute the business to a CRAT—receiving a fixed annual income stream for their lifetime or 20 years (whichever is shorter), with the remainder going to their alma mater.

Once inside the CRAT, the business is then sold. As a result, the CRAT is not taxed on the capital gains. The CRAT pays the couple a fixed annuity of $1.4 million—totaling about $28 million over the course of 20 years. The couple receives a $2.1 million charitable deduction for the actuarial value of the remainder interest. The proceeds from the sale are then invested in a portfolio of securities (stocks, bonds, etc.). Assuming the portfolio grows by 6% annually, about $16 million will eventually be left to their alma mater.

Case study #2: Funding a CRT with appreciated stock

An investor in her 40s purchased $6 million of stock in a new tech company. After a few years, those shares were worth $18 million. If she cashed out, she would have to pay capital gains taxes of 23.8% on the $12 million of appreciation—leaving her with a tax bill just shy of $3 million.

Instead, she and her advisors set up a CRUT, which enables her to add more assets in the future. The CRUT will last the shorter of 20 years or her lifetime. She will receive 12% of the assets each year—or just over $2 million the first year. Over the course of 20 years, assuming a return of 8% annually, she will receive approximately $29 million. She will receive a $1.8 million charitable deduction. And at the end of the 20-year term, the charitable organization she chose will receive approximately $7 million.

Conclusion

Charitable remainder trusts can be extremely useful wealth planning tools if you’re philanthropically minded and have significant assets. They can allow you to have a major impact on a charity you value—potentially a much bigger impact than you could have otherwise—while also benefiting your bottom line significantly in the forms of lower taxes and a regular income stream.

That said, there can be many details and nuances to CRTs that need to be navigated. The importance of working with an expert in charitable wealth planning cannot be overstated here—as setting up a CRT incorrectly can cause the IRS to negate the tax benefits you can get, as noted above.

Best bet: Make sure your advisor is a professional with expertise in the areas of charitable giving and philanthropic wealth planning—or that they have access to such a professional via a network of experts.